The Cosyne Chronicles, vol. 2

Instead of paying attention to the current talk, I’m going to spend some time writing up some of the things I picked up from this morning. Then I’ll use this file to take further notes. This, again, is just what I managed to pick up and understand.

Sensory processing (very partial)

For a lot of the talks of the first sessions, what I could follow properly was the research question being posed, and a lot less so for the answers to those questions. Anyway, a few points just to get a feeling of the topics:

- Suppose we learn to fear something, like a certain kind of snake. Will this make us fear all snakes, or will it make us particularly good at telling dangerous snakes apart from innocuous ones? It turns out sometimes animals show specialisation of fear and improved discrimination of stimuli, sometimes generalisation of fear and confusion of stimuli (Aizenberg and Geffen, Nat Neurosci 2013). Acuity to stimulus is anticorrelated with generalisation of fear.

- Consider an area of the cortex. There are cells that respond to certain stimuli, but there are also a lot that don’t seem to respond to particular stimuli, at least during the task we are studying. Instead, they are very variable in they way they respond. How do we make sense of what they are doing?

- (Obviously my favourite) Deep Convolutional Neural Networks have revolutionised artificial vision, taking inspiration from the visual cortex. There have been comparisons between receptive fields of DCNNs and of VC, with very nice coincidence. Here, they compare using a different method. They submit both DCNNs and VC to different kinds of visual stimuli, and build a correlation matrix of the responses of the DCNN to the different images, then the same with VC. Similarity between a neural network layer and a cortex layer (inferotemporal cortex) is measured by measuring the similarity between the two correlation matrices. The result is that not much can be seen with deep networks of 100 or so hidden layers, whereas for ~10, one typically sees a good compatibility in the later layers, in particular the penultimate one. The effect is enhanced if done specifically with the IT face recognition area and a face-trained DCNN (I think this is what I understood).

Neural dynamics

Brent Doiron (Pittsburgh; his name, we learned, is almost impossible to pronounce properly) presented some deeply theoretical work about variability, balanced networks, dimensionality, and slow inhibition. I confess I couldn’t follow the details; in fact, I’m not even sure I understood what he meant by variability. If I understood correctly, one of the problems addressed was that realistic inhibition time constants are slow, so that in balanced network models one ends up into a Synchronous Regular phase, which is unrealistic, as Donald Trump himself noticed (according to Doiron):

The workaround that lets us keep a slower inhibition is using a non-trivial local form of connectivity. The resulting model has a quite complicated phase diagram. Most of the work presented is contained in papers in press or in preparation, but some is already in “The spatial structure of correlated neuronal variability”, Nature Neuroscience 2017.

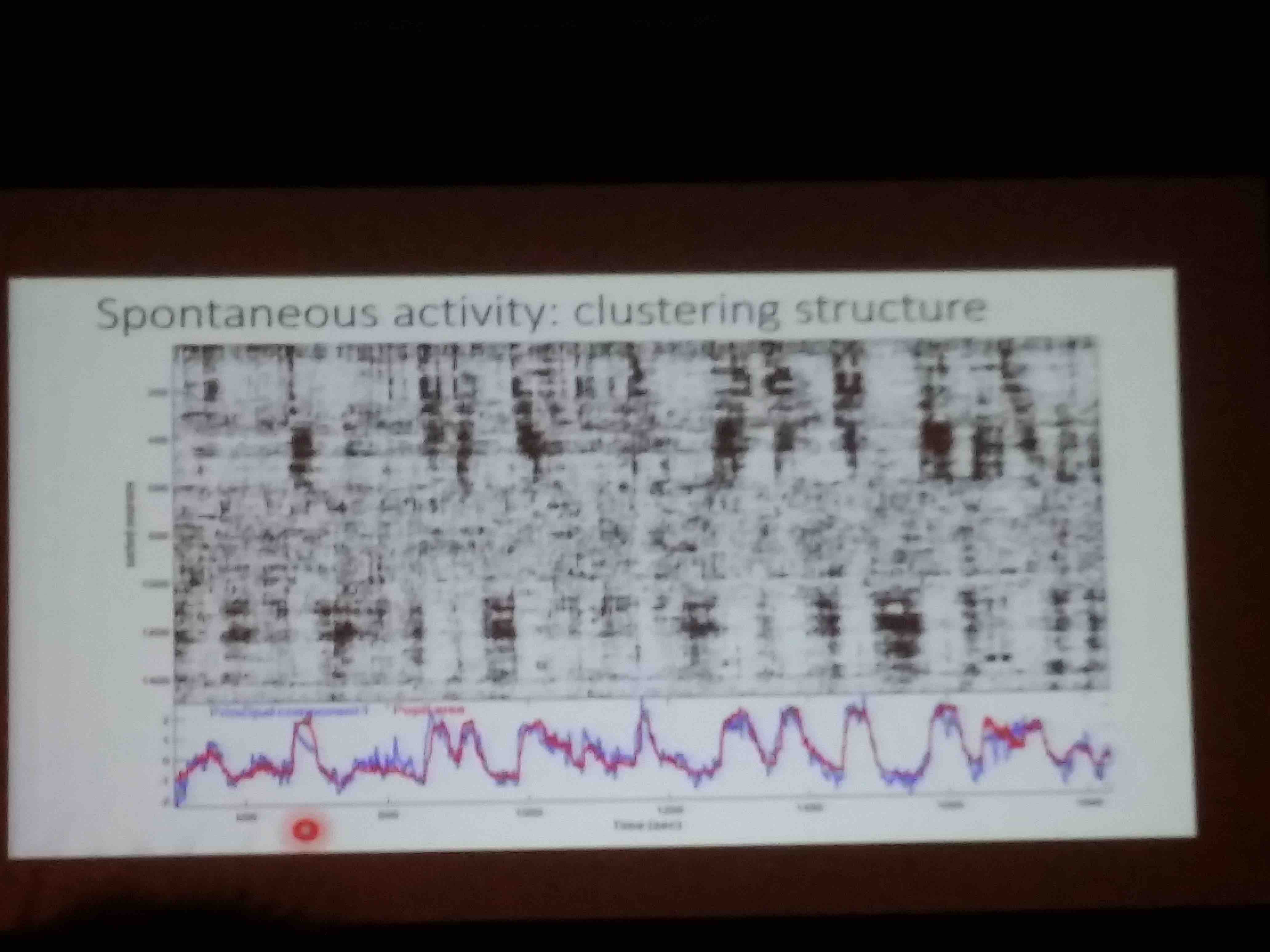

Marius Pachitariu’s (Gatsby, UCL) talk was the one I understood the best today. It revolved around the question of whether the activity of a large neural population can be actually described as low-dimensional or is irreducible. In other words, if I do a Principal Component Analysis of the activity of 10 000 neurons, how many principal components do we need to describe a good amount of the variance? Dozens? Or thousands?

And yes, he does have a way of measuring from 10 000 cells at the same time, with calcium imaging and two-photon microscopy: this is done by sacrificing temporal resolution (down to ~3 Hz). The results:

- Stimulus-driven mouse V1 activity is high dimensional (thousands of dimensions, for 10k neurons).

- Spontaneous V1 activity is low dimensional (50-100 dimensions). This can be made evident by clustering neurons by similarity of their time series, and then showing a raster of those series:

- Principal components of stimulus-driven activity are orthogonal to principal components of spontaneous activity. In fact, that thing that we call spontaneous activity seems to go on undisturbed during stimulation thanks to this.

- Behavioural states (measured by recording mice with a camera) can explain some of the variance of this spontaneous activity. Recordings from other brain areas can too (even better).

Wei Ji Ma’s lunch session

Wei Ji Ma is amazing. And not because he graduated in physics at 17 and got his PhD at 22. Because he decided to make his experience as a scientist open to anyone, for younger students and scientist to benefit from it. He talked for an hour about the struggles he had to face during his academic career, in an extremely sincere and humble way. He talked about his problem with procrastination, with impostor syndrome, with bad student-supervisor relationships with multiple PIs, with changing subject from physics to neuroscience, and all that. He made the audience do the same, and be open about their problems as humans doing science. Interestingly, he organised an entire seminar series, at NYU and occasionally elsewhere, where he asks other senior scientists to share their experiences.

Afternoon sessions

I didn’t take any notes during these sessions, sorry!

Posters

I was extremely tired, I confess I could hardly understand anything at all. A few topics I saw here and there:

- The hypothesis that sleep deprivation pushes network dynamics away from the “critical” state, into the supercritical (bursty) phase. This seems to be the case analysing completely different data, from mice and humans. The interesting thing is that it is known in medicine that epileptic seizures happen more commonly in sleep-deprived patients.

- “Evidence that feedback is required for object identity inference computed by the ventral stream”. I didn’t read the entire poster, but I liked how they put the take-home message in the title.

- Another poster mentioned a “layer-localised learning”. This is another attempt at trying out what I call “local” unsupervised learning rules, which “see” only the pre- and post-synaptic activity, and don’t have access to a global objective function for the entire network as in the case of backprop. This used simple threshold-activated neurons.

- In front of this, another poster (Sejnowski) did the exact opposite: they took a spiking network and were able to train it by gradient descent in order to have it perform task that SNN couldn’t learn before. This was accomplished by a smooth approximation of the spiking dynamics. Interesting as well, I’m not sure for what.

- I saw a couple of posters about “statistical models” of the kind I work on. Both had Gasper Tkacik’s name on them. It seems that the tendency is to find more and more compact models that reproduce the statistics of binned neural activity better and with less computational expense, but I still find little about how to use these models or interpret the parameters once they are inferred. One (“MERP”) was a maximum entropy model where the constraints are the “expected values of sparse random projections of the population activity”. The other was an energy based model with some sort of nonlinearity in the energy.

Enough for today, again there would have been a lot more to learn, but this is what I managed to absorb. Goodnight!